I write this with tears in my eyes and a deep ache in my heart. The news of Pope Francis’ passing feels like a personal loss, as though a spiritual father, a mentor, a brother on the journey has gone ahead. It is difficult to put into words what this man—this holy, humble, courageous man—has meant to me, to the Church, and to our broken, beautiful world.

Pope Francis was a gift—God’s loud whisper in an age of noise, God’s gentle mercy in a time of judgment. His very election was a sign of something new: the name Francis, the choice of simplicity, the call to rebuild the Church—not in bricks and stones, but in heart and soul. From the moment he bowed before the people, asking for their prayers, I knew something in the Spirit was stirring.

What moved me most—and still does—is how Pope Francis embodied the mission of Christ in Luke 4:18–19. He didn’t just read the text about bringing good news to the poor, setting captives free, and proclaiming the Lord’s favor—he lived it. And he called the whole Church to live it too. Under his guidance, the Church rediscovered that its true home is not in grand palaces but in the peripheries. He challenged us to leave behind a “maintenance Church” and become a Church on mission—a field hospital, a mother with an open heart.

Pope Francis was not just a leader of the Church—he was a listener, a storyteller, and a scribe of the Spirit. His teachings were never cold doctrinal proclamations; they were letters of the heart, written in the dust of the road, in the wounds of the poor, in the cries of creation. Each of his documents emerged not from the safety of ivory towers, but from deep listening—to the people, to the earth, to the margins, and to the God who speaks in hidden places.

His first encyclical, Lumen Fidei (The Light of Faith), completed shortly after his election, reminded us that faith is not blind—it is a light, a relational gift, one that opens our eyes to the world, to others, and to the face of the suffering Christ. He reconnected faith with truth, but not in the abstract—truth that walks with people, that loves, that sees, and that transforms.

In Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), he lit a fire in the Church. He called us out of our comfort zones and into the streets. He asked us to become a Church that goes forth—joyful, wounded, merciful. He was clear: an evangelizing Church is one that enters the messiness of people’s lives, especially the poor, and proclaims that God’s mercy is larger than any sin or structure. This document has become, for many of us, a pastoral manifesto—a vision for missionary discipleship rooted in joy, justice, and the smell of the sheep.

Then came Laudato Si’ (Praise Be to You)—a revolutionary encyclical that was not just about the environment but about integral ecology: the deep and inseparable link between the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor. It shattered the illusion that ecology is a side concern and instead made it central to faith. It spoke with the voice of Saint Francis, but also with the voice of the farmer, the fisherfolk, the mother in the squatter settlement, the child breathing polluted air. It called for a deep ecological conversion—a metanoia that reorders our relationship with creation, with one another, and with God.

But to walk this path—to stand with the poor, to hear the earth’s lament, to call the Church into humility—meant confronting powers that resist the Gospel. Pope Francis did not flinch. Time and again, he prophetically challenged the dominant ideologies and powers of our age: the seduction of consumerism, the cold logic of neoliberal economics, the false promises of the technocratic paradigm, and the walls of nationalism that divide and dehumanize. He resisted any attempt to make the Church an ally of empire or a defender of status quo systems that trample the poor and exploit creation.

And just as boldly, he turned his gaze inward, calling out the idols within the Church: the grip of clericalism, the suffocation of legalism, the intoxication of doctrinal rigidity, and the comfort of institutional self-preservation. He saw how easily the Church could become entangled in worldly ambition, clerical privilege, legalism, and cultural conservatism dressed up as tradition. And he confronted this—not with anger, but with the clarity and fire of the Gospel. He spoke truth to power, whether in the halls of governments, within ecclesial institutions, or in the spiritual blindness of comfort. And he bore the cost: vilification, betrayal, deep resistance from those closest to him. Yet he pressed on—rooted in the Poor Christ, the Servant Christ, the Crucified Christ. His legacy is a constant reminder and challenge to us: that the Church must not mirror the world’s values of control, domination, or exclusion, but must embody the disruptive, liberating love of the Gospel.

In Fratelli Tutti (All Brothers & Sisters), he opened up a vision of global fraternity—a world where walls fall and bridges rise. This was not vague utopianism. It was a concrete call to replace the culture of exclusion and competition with a culture of encounter, tenderness, and solidarity. He reminded us that we are all interconnected—not just socially or economically, but spiritually. That the dignity of the Rohingya, the Palestinian, the migrant worker, the Indigenous elder is our responsibility.

In this same spirit, Pope Francis emerged as the most resolute and consistent voice for peace in our time. He condemned war as a failure of humanity and denounced the arms trade as “an industry of death.” For him, peace was not a diplomatic concept but a moral imperative—born from the Gospel and shaped by the dignity of every person. He spoke out against every form of violence—from terrorism to state-sanctioned war, from nuclear weapons to the daily violence of poverty and injustice. He was unafraid to call out the hypocrisies of nations that promote peace while profiting from weapons. Again and again, he insisted that no war is ever just if it ignores the human cost and the path of dialogue. In Fratelli Tutti, he declared clearly: “War can no longer be considered a solution” (FT 258). His advocacy was not abstract—it was bold, concrete, urgent. He stood with refugees, pleaded for ceasefires, and invited the Church to become not only a voice for peace but a builder of peace. And in what we now know to be his final Urbi et Orbi Easter message, he issued one last, impassioned plea for peace—naming the suffering in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Myanmar, and every land where innocent blood cries out to heaven. It was not a political speech, but a lamentation, a prayer, and a Gospel command. In a world driven by conflict, division, and fear, Pope Francis taught us that peace-making is not an option but the very mission of the Church.

With Amoris Laetitia (The Joy of Love), he brought the Gospel into the kitchen and the living room, into the messiness of relationships and family life. He urged pastors to walk with—not ahead of—their people. He emphasized discernment over judgment, process over rigidity. He showed us that God’s grace is not limited to the ideal but is most present in the real—in struggling marriages, imperfect love, and broken homes trying to heal.

In Gaudete et Exsultate (Rejoice and Be Glad), he made holiness accessible. He shattered the image of saints as unreachable icons and invited every person to embrace holiness in the midst of daily life—in how we treat our neighbour, how we care for the poor, how we listen to the Word, and how we resist the idols of ideology, gossip, and indifference. His vision of holiness was deeply pastoral and deeply radical.

With Christus Vivit (Christ is Alive), he spoke with and to the young—not as an old man trying to win relevance, but as a spiritual father who listens and believes in their dreams. He acknowledged their wounds, their energy, their doubts, and their thirst for authenticity. He dared the Church to walk with them—not as instructors, but as fellow pilgrims. He gave us a vision of youth ministry as accompaniment, not indoctrination.

In Querida Amazonia (The Beloved Amazon), he gave voice to the voiceless—to the rivers, the rainforests, and above all to the Indigenous peoples whose wisdom, land, and lives have long been silenced. He honoured their cultures not as curiosities, but as sources of spiritual depth and communal wisdom. He prophetically challenged both the economic powers and the ecclesial structures that have marginalized these communities. This document was an act of ecclesial repentance—poetic and prophetic. It invited us to imagine a Church with an Amazonian face—a Church rooted in the culture of the people it serves.

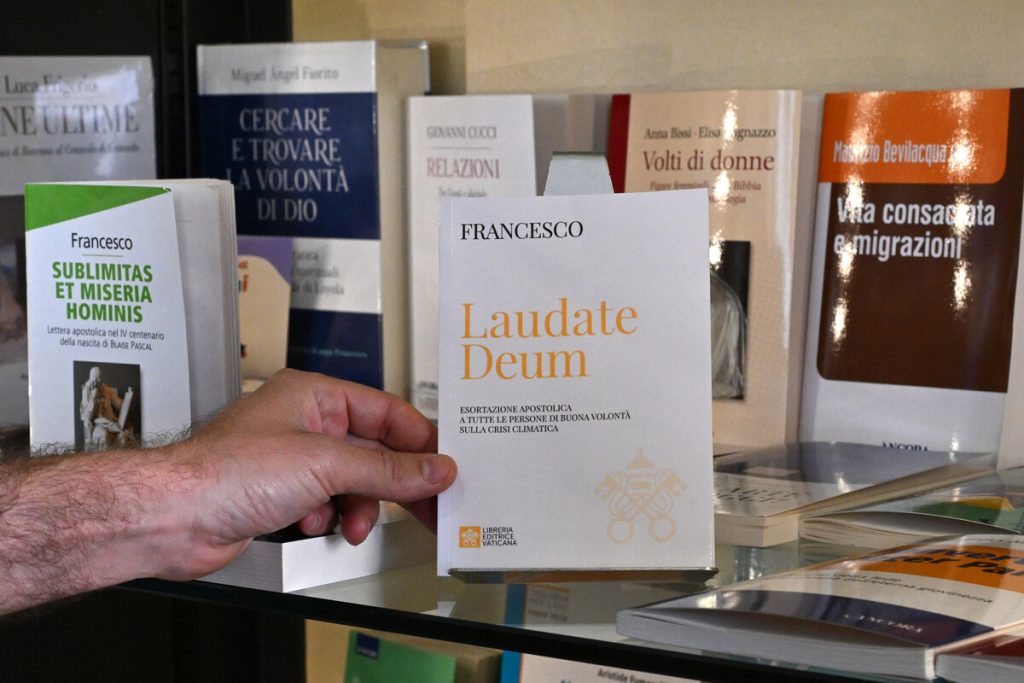

Laudate Deum (Praise God), his follow-up to Laudato Si’, was even more urgent. It was not a gentle call—it was a lament, a warning, a cry. He spoke as one who has seen the world burn and melt and suffocate. He did not mince words. He reminded world leaders and Church leaders alike that delay is complicity, and that ecological justice is not optional for Christians.

And in C’est la Confiance (It Is Confidence), issued on the 150th anniversary of the death of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, he invited us to rediscover trust—not as naïveté, but as spiritual boldness. At a time of global anxiety, division, and suspicion, he pointed us back to the simple, powerful surrender to the heart of God. He taught us, once again, that holiness is not found in perfection but in trusting love.

Finally, Dilexit Nos (He Loved Us), his last encyclical, was a love letter to the world. “He loved us first,” it said—not with conditions, but with infinite tenderness. In it, he connected the heart of the Gospel to the heart of the poor, the broken, and the forgotten. It was as if he were saying one last time: Everything I’ve taught, everything I’ve lived—comes down to this. God loves. God loves. God loves.

These documents are not merely teachings—they are invitations. Invitations to become Church in a new way: listening, walking, opening, daring. They echo his deepest dream: that the margin becomes the centre. That those who have been pushed aside—the poor, the Indigenous, the migrant, the wounded—become the heart of the Church. And that the Church itself becomes a living sacrament of mercy, justice, and joy.

This dream, this Gospel-shaped hope, found its clearest path forward in the model of synodality. And that was the defining gift of Pope Francis to the Church—his tireless call to synodality: a Church that listens, walks, and discerns together. For him, synodality was not a programme or an event—it was the very shape of the Church, rooted in the life of the Trinity and the mystery of communion. It was how the Spirit moves among the People of God—not just through the hierarchy, but through every baptized person. He reminded us that “everyone has something to learn and something to say.” Through the Synod on Synodality, he called the Church to become less of a pyramid and more of a circle—where the margins speak, the centre listens, and the whole Body of Christ moves together. It was a spiritual revolution, one that trusted the voice of the people and the presence of God in conversation. He empowered laypeople, especially women and young people, to be protagonists—not just recipients—of the Church’s mission. Synodality is Pope Francis’ legacy of hope: a Church that breathes with both lungs, that hears the Spirit in the cries of the world, and that walks forward together—not as strangers, but as pilgrims and friends.

For me as a priest, his pontificate was a personal affirmation—a light on my path. His insistence on mercy, justice, accompaniment, and humility gave me the courage to continue walking with the people entrusted to me. His deep love for the poor, the refugee, the migrant, the outcast—his insistence that they are the privileged place of encounter with Christ—rekindled my own vocation again and again.

And in my role in Caritas Malaysia, I saw how his vision breathed life into our mission. He helped us believe that love—caritas—is not a sentiment but a movement, a mission, a way of being Church. He united social justice and spirituality in ways that inspired and stretched us all.

Yes, he was prophetic. And prophets are never comfortable. He unsettled us. He disturbed the status quo. He called us out of a hierarchical, patriarchal mindset and into a servant model, a synodal model, an incarnational way of being. He reminded us that the Church is not an institution to be protected, but a body to be broken and shared.

We are now living the Jubilee Year of 2025—a year Pope Francis himself named as a time for healing, renewal, and journeying together as Pilgrims of Hope. In many ways, his entire pontificate was a preparation for this moment. He taught us how to walk humbly with one another, how to accompany the wounded, how to listen to the Spirit and dream of a Church that breathes with the hope of the Gospel. His life was a pilgrimage of mercy and mission—a path that now calls each of us to continue walking. May this Jubilee Year become the living echo of his voice, his tears, his courage, and his love—a sacred time to rise and walk forward together, bearing light where there is shadow, and hope where there is fear.

Today, I grieve. I feel the loss very, very deeply. But I also give thanks with my whole being. I thank God for this Jesuit Pope who smelled of the sheep, who spoke plainly, who knelt to wash feet, who laughed and cried and walked with the people. He made me believe—again and again—that the Spirit is alive in the Church, and that Jesus truly is the centre.

And because we are still in the Easter season, I hold on to hope. The tomb is empty. Life has conquered death. Pope Francis believed in a Church that always begins again, that rises with Christ, that walks with the excluded, that listens to the Spirit. And now, as he rests in the arms of the Risen One, I pray that we may rise—to continue his mission, his dream, and the Gospel of Christ he so faithfully lived and proclaimed.

May his legacy not be shelved but lived.

May his memory be more than words, but a fire that propels us forward.

May his life echo in the hearts of a new generation of believers, dreamers, and servants.

Thank you, dear Pope Francis. For everything.

I love you, and I will miss you terribly.

You were Christ for us.

You were Christ with us.

And now, you are with Christ.

Rest in the peace of the poor Man of Nazareth whom you loved so deeply.

Fabian Dicom is a diocesan priest of the Diocese of Penang, Malaysia, with 29 years of pastoral ministry. He currently serves as the National Director of Caritas Malaysia. Inspired by the life and vision of Pope Francis, he believes the Church must be a community rooted in justice, compassion, and hope—especially for those at the margins.